Author’s Note: This article is part one of a series of articles dealing with the kidnapping of Chowchilla school children on July 15, 1976. They were taken to a rock quarry four miles west of Livermore, where they were put into an underground dungeon. About five miles east of the quarry was the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory which did a lot of work researching and developing nuclear weapons. It was also a major MK-Ultra center. Nine days prior to the kidnapping on July 6, the Laboratory started receiving a powerful shortwave signal from the Soviet Union called Woodpecker. Although Cold War enemies, the United States and the Soviet Union had secretly formed a partnership to discover new techniques of mind control, using over-the-horizon radar. To secure children needed for mind control experimentation was one purpose of the kidnapping. Another was to create a distraction event to slow down the momentum of Jimmy Carter, an avowed opponent of the CIA, who had a strong lead against President Gerald Ford in his bid to win the White House.

The kidnapping of twenty-six school children from the farming community of Chowchilla, California on Thursday, July 15, 1976 was a carefully timed event, coinciding with the most dramatic moment of the Democratic National Convention being held in New York City – that moment when Governor Jimmy Carter stepped up to the podium to accept the presidential nomination of the Democratic Party. The disappearance of the children became a national sensation and overshadowed and minimized news coverage that Carter was depending on to kick off his race for the White House.

The second to the last day of school at Dairyland Elementary was sunny and warm. A field trip to the Madera County Fairgrounds allowed the children to spend the day frolicking in the swimming pool. When they got back to school, some were still wearing their swimsuits. At 3:45 pm, thirty-one children, ages five to fourteen, got on Frank Ray’s bus to go home. Traveling on ruler-straight roads through cotton fields and almond groves, he dropped off five at three separate stops. Remaining on the bus were nineteen girls and seven boys.

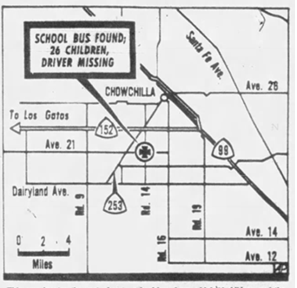

The above map indicates the spot where the bus was stopped by the kidnappers.

At 4:15 pm Ray was proceeding west on Avenue 21 toward the intersection of Road 15, when he was stopped by a late-model Dodge van, white in color, straddling the road with its passenger door open. A man wearing a nylon stocking mask jumped out, brandishing a double-barrel shotgun and revolver. In a deep voice he demanded that the door be opened. Once he got in, he told Ray to go to the back of the bus.

He was 6 foot 1 or 2, medium to heavy build, about 50 years old, 220 pounds. He wore white gloves, a tan short-sleeve shirt, light tan corduroy pants, cowboy boots, and a brown belt with horsehead buckle. A green wreath tattoo with the initials “N.O.W.” in the center was on his right arm. Other than what he initially said to the bus driver, he never spoke a word. “He just kind of glared at us,” recalled one student. Ten-year-old Jeffrey Brown observed more details: He was “tall, kind of blocky. He was broad-shouldered, eyes far apart and baggy. The guy looked like he was real solid, and he had yellow pimples on his face. His chin was kind of square. He had light brown hair. He had kind of a pug nose that’s wide – sort of flattened out as though broken. He had a short gun. It looked like a sawed-off shotgun.”

Two more men wearing stocking masks got on the bus. A young man, about 23 to 27 years old, was carrying a pump shotgun. He was very thin, 5 foot 7, collar length brown hair, light complexion, moustache, and a hairy mole on the right side of his chin. He wore white gloves, a white T-shirt, blue corduroy pants, cowboy boots, and a silver watch. On his right wrist was a blue-green tattoo. He spoke with a foreign accent, possibly French, although he might have been trying to disguise his voice. A fellow kidnapper called him “Jerry.” When an eight-year-old girl heard the name and saw to whom they were referring, she asked, “Jerry McCune?” The disturbed reaction of the abductors to the little girl’s question is an indication that she had indeed made a positive identification.

The third man wore black, thick-framed glasses over his mask. He was unarmed, about 5 foot 6, somewhere between 28 and 45 years old. He had a white straw hat, white gloves, a blue-checkered shirt, brown pants, and blue tennis shoes. Jeffrey Brown said, “He had a round chin and looked kind of skinny, scrawny. He had black hair. He had sideburns, a one-inch scar on his right cheek, and a chipped front tooth.” To disguise his skinny appearance, he had “a pillow stuffed in his shirt to make him look fat.”

The man wearing glasses settled into the driver’s seat and took control of the wheel. The white van was driven by a fourth kidnapper, who took a position behind the bus. They travelled about a mile west along Avenue 21 before turning left into a dry creek bed called the Berenda Slough on the south side of the road. A man in a dark green van met his fellow abductors at the creek bed. The driver of the white van backed up to the rear the bus, and a group of children, about half the total number, were herded through the rear exit door into the van. The white van then pulled away, and a green van, parked nearby, took its place. Both vans were equipped with CB radio antennae. As Ray and the remaining children got into the green van, he caught sight of the license plate of the white van.

Aerial view of the bamboo grove where kidnappers abandoned the school bus.

After the back doors were closed and locked, the captives found themselves enveloped in darkness so black they could not see anything. Modifications had been made to eliminate any openings by which they could see what was going on outside. The windows were covered with paint, and cardboard and plywood were mounted on the walls.

The two vans exited the slough and headed down the road toward the main highway. Thus began a long and wearisome ride lasting eleven hours. The children tried to keep up their spirits with songs like “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands.” This eventually became “If you’re sad and you know it . . . “ Some of the smaller children were vomiting because of motion sickness. No food or water was offered to the captives. Ray tried to calm those who were crying, but others settled down into fatalistic despondency, saying, “We are going to die.” They never heard any audible clues of location such as city traffic noises, train horns, or railroad crossing signals. They never stopped at a gas station. Those who needed to urinate had to do so in their pants. During the course of the journey, the abductors made four stops. At each stop, the smell of gas coming from outside indicated to the captives that more fuel was being added to the gas tanks. A third van, unseen by the captives, was carrying a supply of gas cans to re-fuel the other two.

Meanwhile, back in Chowchilla, school superintendent Lee Tatom was getting phone calls from mothers wondering what happened to their children. Tatom got into his car to find out. He started at Dairyland Elementary and traced the route Ray would have taken from beginning to end. He could find neither the bus nor its occupants. Tatom was puzzled. Ray was a very dependable man, having driven school buses for 26 years. Something must be terribly wrong. Tatom called the police.

More than fifty people, including police officers, sheriff’s deputies, frantic parents, concerned townspeople, some on horseback, some in cars or pickup trucks fanned out in all directions. Aiding them were two men who volunteered to fly their private planes. In spite of the large number of people involved, the amount of territory they covered, and the diligence of their efforts, no trace of the children, their driver, or the bus could be found.

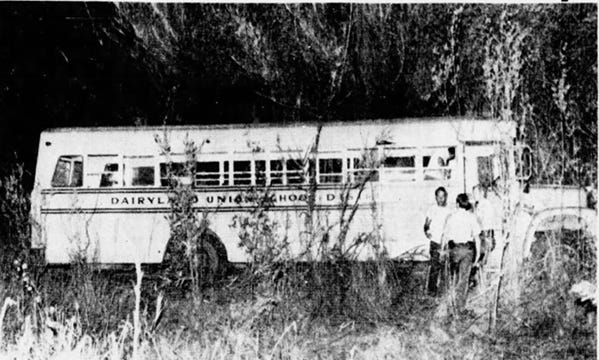

Finally, at 7:15 pm, a pilot spotted the missing bus hidden in a dense thicket of bamboo in a slough between a corn field and an almond grove. When ground searchers arrived, they discovered that the bus was empty and the ignition key was missing. Swimwear and towels were found on the bus. No footprints were on the ground, but there were two sets of tire tracks superimposed on the bus tracks.

Police and parents inspect the school bus found in the Berenda Slough.

Law enforcement authorities were reluctant to label the disappearance a kidnapping, but fears for the children’s safety increased with each passing hour. The Chowchilla mystery quickly became a major news story on television news programs, competing with news coverage of the Democratic Convention in New York City.

At 10:30 pm EST (7:30 California time) three thousand delegates at the Madison Square Garden convention hall watched Jimmy Carter make his way down the aisle to the podium and kiss his eight-year-old daughter Amy. Roseanne Carter came out in a red dress and gave an enthusiastic greeting to the delegates. Carter, now alone, smiled and waved through an eight-minute roaring welcome. During his 38-minute acceptance speech he made it clear that he will not let American voters forget the sins of Watergate, the pardon of Nixon, and the scandalous illegalities of the CIA:

“We can have an American Government that has turned away from scandal and corruption and official cynicism and is once again as decent and competent as our people. We can have an American Government that does not oppress or spy on its own people but respects our dignity and our privacy and our right to be let alone.”

Carter was followed by Martin Luther King, Sr., who gave a fiery benediction. The convention ended with delegates joining hands and singing “We Shall Overcome.”

These were the final hours of a stirring week for the Democrats. Barbara Jordan, the first African American woman to be the keynote speaker, was given a thunderous standing ovation from delegates who saw in her the memory of civil rights battles in previous conventions. The crowd rose and cheered when Senator Ted Kennedy was introduced and a second time when Ethel Kennedy and her son Joseph were introduced. Carter’s pick for running mate, Senator Walter Mondale, a former member of the Church Committee that sought to curtail the CIA’s covert activities, was given a standing ovation. Many heartfelt demonstrations of unity and racial inclusiveness were expressed. The convention was notably harmonious in stark contrast to the bitter and divisive conventions of 1968 and 1972. Carter’s campaign to defeat incumbent President Gerald Ford was off to a great start.

As King was delivering his benediction in New York, the two vans carrying the Chowchilla captives had been on the road for five hours. It was not until six hours later at 3:30 am, that the vans reached their destination. The back doors of the green van were opened to reveal a tent-like tarpaulin canopy that extended out from the back of the van. The purpose of the canopy was to keep the victims from knowing their location. One of the kidnappers yelled “Where is the bus driver? We want you out first.” As he got out, they asked for his name and age. Then they wanted his pants and boots, which he gave them. On the ground was a piece of dirt-camouflaged canvas, which they removed. Underneath was a three-foot-wide hole.

Ray was forced to descend a ladder into an underground chamber. He was followed by the children, who went in, one by one. As they went in, a man asked and noted their names, ages, parents’ names on a fast-food bag, and took from each an article of clothing, a shoe, or a girl’s purse.

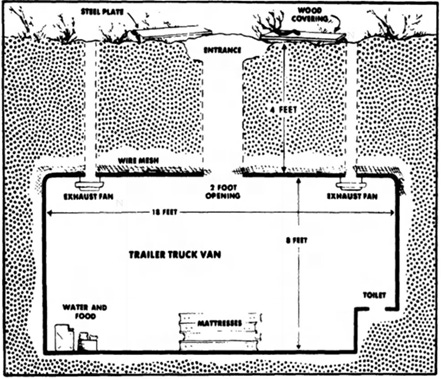

Using a flashlight given to him to guide the children in, Ray could see that they were inside the trailer of a truck about eight feet wide and sixteen feet long. Mesh fencing covered the interior walls, and six 4×4 vertical posts extended eight feet from floor to ceiling. Ray saw mattresses and box springs, two wooden boxes with holes on top that served as improvised toilets, ten five-gallon containers of water, boxes of dry breakfast cereal, bags of potato chips, and two loaves of bread. There was enough food and water to last at least a day, maybe two. Mounted in two holes, one cut through the front and the other through the right side, were battery-operated fans that circulated air through flexible hoses, four inches in diameter. (One hose was thirty-five-feet long, hidden from view in the branches of a tree.)

Artist’s drawing printed in newspapers gives an idea of the layout of the buried truck van. The drawing erroneously shows the vents coming out of the roof.. Actually one vent came out of the front and another vent came out of the right side.

After pulling up the ladder, the captors tossed down a roll of toilet paper. Then they put a heavy metal plate on top of the hole and weighed it down with a wooden box full of dirt and a pair of hundred-pound truck batteries. Then they used wire-cutters to cut through cables holding a wire-mesh fence, thus releasing an avalanche of dirt and gravel on the roof of the trailer.

Inside the trailer, the captives watched fearfully as the ceiling buckled from the weight of earthen material. It would have collapsed had not the six vertical posts held it up.

Trapped in the darkness of their dungeon with only a flashlight and a candle for illumination, the captives could hear the voices and footsteps of kidnappers milling around above them. As the hours dragged on, the children became hysterical from terror and despair. The makeshift ventilation system was inadequate for proper airflow, and the heat inside became oppressive. One of the vent fans stopped working, forcing the children to gather around the one vent that was still blowing. Many were coughing from the lack of fresh air. Others were vomiting amid odors of urine and filth. One girl fainted three times. Ray poured water on the children to cool them off.

In the world outside, the Chowchilla children became a huge news story – the largest mass kidnapping in the history of the United States. Carter’s nomination speech from the previous night, which in normal circumstances would have garnered big headlines, was pushed down to second place. A state-wide all-points bulletin was issued by the Madera County Sheriff’s office for three vans traveling together on State Highway 152, heading west. One van was painted white with blue and gold trim. For several days it was seen loitering along the bus route. It was last seen near Ray’s third and last stop on Avenue 18.

Lawmen from many parts of the state joined the search for the missing children and their driver. Some conducted a house-to-house search in Chowchilla. Officers of the Highway Patrol stopped and checked vans with more than one occupant. A team of specially trained bloodhounds was on its way from Philadelphia. The FBI entered the case with 48 agents on the scene and 29 more enroute. Overhead, planes and helicopters from various agencies crisscrossed the skies over the San Joaquin Valley.

Law enforcement authorities speculated that the perpetrators were either left-wing terrorists, black radicals, or anti-capitalist hippies. An anonymous person called the San Francisco Chronicle and said “Chowchilla, Weatherman,” a radical group that preached violence as a form of political protest. The news media began to focus on the New World Liberation Front, a revolutionary SLA-style terrorist organization that triggered bombs in various places such as the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, a Safeway Store in Novato, and a PG&E office building in Roseville. Although readily taking credit for the bombings, Ande Lougher, a spokeswoman for the group, adamantly denied that they had anything to do with the kidnapping. Nonetheless, sheriff’s deputies in Santa Clara County were put on the alert that the missing captives might have been taken to the nearby Santa Cruz Mountains, where the NWLF had its headquarters. (The sparely populated Santa Cruz Mountains was a well-known haven for hippies, black radicals, and leftist extremists.)

Meanwhile, the people of Chowchilla prayed for their children. God heard their prayers, and a miracle occurred.

After some hours passed, the footsteps of the abductors ceased. They apparently left the area. After waiting for what seemed an eternity (in case they returned), the oldest boy, Mike Marshall, age fourteen, decided he was going to dig his way to freedom. The bus driver, who had already given up in hopeless despair, discouraged him from trying and told him that their time had come “to kick the bucket.” Mike refused to give up. He wasn’t going to die without at least trying to find a way out.

After piling up mattresses to reach the plate covering the hole in the ceiling, Mike realized he needed something to hold the plate up so that he could have access to the dirt around it. He got down, kicked one of the box springs apart, and found a suitable stick of wood, eighteen inches long. The next step was to insert the stick between the plate and the roof of the trailer. Using all his might, he tried to lift the plate, but he was not strong enough. At last, Ray and another boy, ten-year-old Roberto Gonzales, came to help. Using all their combined strength, they managed to open a gap sufficient to push the stick in. This gave them the room they needed to start excavating the dirt. As they dug, increasing amounts of earth trickled down. Periodically the diggers doused themselves with water to keep from passing out in the suffocating heat.

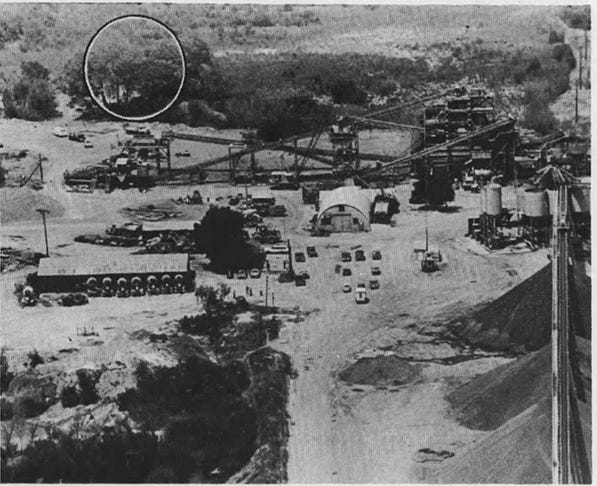

After five hours of digging, their efforts were rewarded by a streak of sunlight and cool, fresh air. The removal of more dirt enabled them to lift the plate up and flop it over. Roberto was the first one out, followed by Mike. It was 7:00 pm, and the sun was still up. Together the two boys looked around and saw the heavy machinery of a rock quarry. It had been sixteen hours since they descended into their underground tomb.

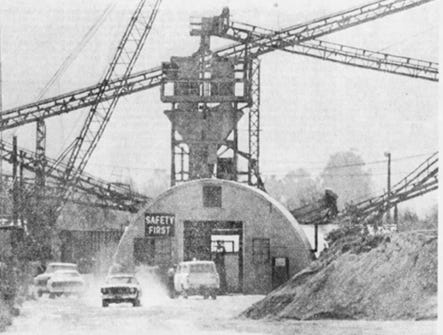

The rock quarry where the vhildren and their driver were held prisoner. The circle indicates the area where the trailer was buried.

The location of the trailer is pinpointed by arrow. It is approximately 100 yards west of Isabel Avenue and hidden near large trees.

They saw a security guard, ran to him, and implored him to help get the others out. He followed the two boys to the hole, but for some reason, he retreated from the scene and was never heard from again. (Several days later, reporters seeking more information on the security guard were told that he went on a two-week vacation and that he could not be reached.)

Standing on the piled-up mattresses, Ray heaved up the children, one by one, while Mike and Roberto stood by to pull them out. By the time Ray, the last one, climbed out, the sun was setting, and it was getting cold. Some frightened children hid in the bushes, but most clustered around Ray as he roamed around the quarry seeking for someone to help them. About two hundred yards from where they started, he saw a welder working high up on a quarry mill tower. Ray ran toward the stairs, climbed partly up, and hollered up at him, “We’re the ones from Chowchilla.” The startled welder, Walter Enns, could hardly believe what he saw: a swarm of filthy kids led by an even filthier man dressed only in a polo shirt, jockey shorts, and socks. Enns pressed a button to call for another worker, who was in a shop nearby, and told him to call the sheriff. Enns then led Ray and the children to a nearby Quonset hut and gave them all drinks. They were so thirsty that they completely emptied a soda pop vending machine. He also found a pair of overalls, which he gave to Ray.

Quonset hut where Ray and the children were taken to.

Walter Enns shown at trial.

The call to the sheriff’s office came in around 8:15. The missing children had been found, and they were at the California Rock and Gravel Quarry located about four miles west of Livermore at the southwest corner of Isabel Avenue and Stanley Boulevard. (The quarry is about an hour and a half from Chowchilla using the most direct route. The kidnappers deliberately prolonged the trip to eleven hours by aimlessly travelling back and forth along the highways.)

The fire department got a similar call at 8:24. Police cars and fire trucks were dispatched to the quarry, arriving fifteen minutes later. The firemen brought out blankets to cover the shivering children and tried to comfort the younger ones who were still screaming and crying.

Sheriff’s Lt. Ed Volpe, the first lawman on the scene, could see that Ray and the children were in a “state of shock and paranoia.” Ray was “glassy-eyed and hyper,” confused, disoriented, and had difficulty communicating. Volpe said, “He couldn’t sit still. He was sweating. He said he was thirsty and threw away a can of soda. I had difficulty getting him to concentrate on questions. He was just a bundle of nerves. He couldn’t sit still for thirty seconds.”

The children were also highly agitated. “They were so frightened they wouldn’t talk to me,” said Volpe. “They were afraid that my men and I were kidnappers in disguise and would bury them again,” Volpe said. “All I can say is that the scene was one of hysteria, paranoia, screaming, laughing, and crying. They were highly excitable, their eyes were glassy.” The situation was so chaotic that Volpe called his wife at home to come and help him with the smaller children. When a bus arrived to pick up the children, some were so frightened that, at first, they refused to get on. Volpe and his wife had to pick up several of the more resistant ones and carry them on board. The bus proceeded through a crowd numbering thousands of spectators who heard the news on radio and television. Cars were lined up for more than a mile on Stanley Boulvard. Police used bullhorns to tell people to get back in their cars and go home.

The children were taken to the Santa Rita prison, where they were held in the rehabilitation center. Ray did not go with them but stayed behind to talk with the police and the FBI. At 10:00 he was also taken to the rehabilitation center. The ex-captives were met by a swarm of newsmen who wanted to take their pictures and get interviews. A reporter for the Associated Press did not fail to catch the irony of the situation. Despite what was touted by Lt. Governor Mervyn Dymally as the largest joint federal-state search operation in the history of California, involving thousands of lawmen from numerous agencies using vehicles, planes, helicopters, and bloodhounds, it turned out in the end that the children and their bus driver saved themselves – by themselves.

By midnight, they had all been examined by doctors, declared healthy, washed, clothed in adult-sized prison garb, interviewed, and fed a meal of hamburgers and french fires. At about 1:35 am, Ray and the children boarded a Greyhound bus to take them back to Chowchilla. They arrived at the Chowchilla police station at 4:55 am, met by two hundred friends and relatives who greeted them with tumultuous cheers.

School bus driver Frank Ray back in Chowchilla, wearing the overalls given to him by Walter Enns.

Mike Marshall back in Chowchilla.

The following day, July 18, three men belonging to the Audubon Society were out bird-watching in the Santa Cruz Mountains when they spotted a plastic suitcase on an embankment alongside Highway 9 near Saratoga (about 150 miles from Chowchilla). Inside the suitcase were children’s clothes, shoes, and notebooks. They turned over the suitcase to the Santa Clara Sheriff’s Office. Deputy Mike Alford checked out the various items and found that they belonged to the kidnap victims. He then went out to the scene of discovery himself and found nearby a tarpaulin-covered cache containing towels, newspapers, computer printout paper, but more significantly Ray’s trousers, boots, and volunteer fireman identification card. Even though the victims’ belongings were found on Sunday, they were probably planted prior to their escape on Friday.

It appeared that the location of the discovered miscellaneous items pointed toward a person or group living nearby, probably some hippie anarchists. This would confirm the initial belief that left-wing revolutionaries were the culprits. But the information that came from the victims themselves led in the opposite direction – to a right-wing conspiracy organized and funded by an intelligence agency.

The surprise appearance of the Chowchilla children and their bus driver was an electrifying moment rarely seen in the history of deep state conspiracies. What normally happens, what was supposed to happen, is the quick apprehension – or preferably elimination – of a suitable fall guy. Carefully planted evidence in key locations would lead investigators away from the true criminals and focus on an innocent party. Assembling the fake evidence to make a plausible case would be a tight-knit combination of local police, the FBI, the district attorney, the lawyers, the judges, crime lab technicians, medical examiners, and psychological profile experts. The controlled mainstream media would then present their findings in the form of an air-tight cover story. Inconvenient facts would be suppressed, and eyewitnesses not aligned with the accepted narrative would be subdued or eliminated.

The perpetrators found themselves in an unexpectedly precarious position – caught out in the open with no place to hide. The conspiracy was unraveling at an alarming rate. It was only a matter of time before arrests would be made, televised trials, imprisonments and/or public executions of prominent persons. The Chowchilla event had the potential of becoming a fundamental turning point in the history of the United States, clearing out the moral rot, corruption, and cynicism in a way that Carter never anticipated when he made his acceptance speech at Madison Square Gardens.